Lecture: Formation of modern European civilization. Renaissance and Reformation. The formation of modern European civilization. Renaissance and Reformation Significance of the Renaissance and Reformation for economic development

PROTESTANTISM

The Reformation gave rise to the third, after Orthodoxy and Catholicism, a branch of Christianity - Protestantism. This is a collection of independent and diverse religions, churches, differing from each other in dogmatic and canonical features. Protestants do not recognize Catholic purgatory, they reject Orthodox and Catholic saints, angels, the Virgin; the Christian triune god occupies a completely monopoly position among them. The main difference between Protestantism and Catholicism and Orthodoxy is the doctrine of the direct connection between God and man. According to the Protestants, grace comes to a person from God, bypassing the church, "salvation" is achieved only through the personal faith of a person and the will of God. This doctrine undermined the dominance of spiritual power over the secular and the dominant role of the church and the pope, freed a person from feudal oppression and awakened in him a sense of dignity. In connection with a different attitude of man to God, not only the clergy and the church, but also the religious cult in Protestantism is given a secondary place. There is no worship of relics and icons, the number of sacraments is reduced to two (baptism and communion), worship, as a rule, consists of sermons, joint prayers and singing of psalms. Formally, Protestantism is based on the Bible, but in fact every Protestant religion has its own creeds, authorities, "sacred" books. Modern Protestantism is spread mainly in the Scandinavian countries, Germany, Switzerland, England and the USA, Canada, Australia, etc.

MARTIN LUTHER

The reform movement in the person of Martin Luther (1483 - 1546) had its outstanding representative. This German reformer, the founder of German Protestantism, who was influenced by the mystic and the teachings of Jan Hus, was not a philosopher and thinker. The reformer's parents came from Thuringian tax-paying peasants. In 1537, in one of his "table speeches," Luther spoke of his childhood and adolescence as follows: "My parents kept me in strictness, amounting to intimidation. For a single nut, which I somehow coveted, my mother whipped me to the point of blood. With this harsh treatment, they eventually pushed me into the monastery. Although they sincerely believed that they were doing me well, I was intimidated by them to the point of timidity. “In my opinion,” writes E.Yu. Solovyov, Luther's decision to go to a monastery can be considered as the ultimate expression of that disappointment in the possibilities of practical success, which was generally characteristic of the entrepreneurial-burgher class, thrown into a situation of merchant-feudal robbery, devoid of any religious and moral support. At the same time, this decision also contains an element of unbroken burgher pride: the desire to achieve one's own on the path of ascetic practicality "approved by God." In July 1505, Luther retired to an Augustinian monastery, famous for its strict rites. However, the result of his various ascetic efforts was deplorable. No matter what Luther did, the consciousness of God-forsakenness did not leave him. In 1512, Luther again suffered an attack of melancholy (it should be noted that at the age of 29 Luther became a doctor of theology and a subprior of the Wittenberg Augustinian convention, these were church-approved successes at that time), and he retired to a cell, where he began to work on compiling commentaries on the Latin text of the Psalms. Unexpectedly for himself, he discovered a new meaning for long-known texts, which led to a "revolution" in Luther's mind of understanding the problem of justification and salvation. "Luther realized himself directly involved in God through that very judging ability of conscience, which just testified to his God-forsakenness." After Luther begins to realize that the development of additional "Christian merits" in the monastery is an empty business. And already in 1515-1516, he questions the foundations of monastic - ascetic piety. The beginning of the reform movement was the event that took place in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517, when Luther promulgated his historic 95 Theses against the sale of indulgences. At that time, there was a saying: "All sins are forgiven by the Church, except for one - the lack of money." The main motive of the "Theses" is the motive of internal repentance and contrition, opposed to any kind of external activity, any deeds, exploits and merits.

The central thought of the Theses is as follows: the idea of expiatory donations is profoundly alien to the Gospel of Christ; the god of the gospel does not require anything from a person who has sinned, except sincere repentance for what he has done. The main idea of the "Theses" - only repentance to God - prompted the believer to the idea that all church-feudal property is an illegal and forcibly acquired property. The denunciation of the hidden impiety of the church, led by the pope, before God brought to the side of Luther all those dissatisfied with the rule of corrupt Rome. Luther does not recognize mediators between God and man; he rejects the church hierarchy along with the pope. He rejected the division of society into laity and priests, since there is not a word about this in Scripture. Luther wrote his first theological works in 1515-1516. In his publications "Explanation to the dispute ...", "Conversation about forgiveness and mercy", etc., he explained the meaning of his "Theses". Since 1518, Rome launched an inquisitorial process against Luther, he was excommunicated from the church. Luther rejected most of the sacraments, saints and angels, the cult of the Virgin, the worship of icons and holy relics. All the ways of salvation are only in the personal faith of a person. Affirming the indisputability of the authority of Scripture, Luther insisted on the right of every believer to have his own understanding of faith and morality, on freedom of conscience, he himself translated it into German. Already in 1519, Luther abandoned the medieval notion of the text of Scripture as a mysterious cipher that could not be understood without knowledge of the established church interpretation. The Bible is open to everyone, and no interpretation of it can be recognized as heretical unless it is refuted by obvious reasonable arguments.

In August - November 1520, Luther's publications were published, which amounted to a kind of reformist theology: "To the Christian nobility of the German nation ...", "On the Babylonian captivity of the church" and "On the freedom of a Christian." They outlined a program for a radical transformation of the church organization and "found formulas for a complete moral and religious disengagement from the papacy." Luther declares war on ecclesiastical-feudal centralism. 15-16 centuries - the time of the crisis of scholasticism and the growing dissatisfaction with it on the part of humanists and pioneers of natural science. Luther declared his attitude to scholasticism in the summer of 1517 and touches on this topic in his programmatic essay The Heidelberg Disputation (1518). God, in his understanding, is defined as an unknowable thing, absolutely transcendent in relation to the ability to rationally comprehend the world. Any attempt to investigate what God is, or at least prove that he exists, the reformer considers futile and false. God is only known to man insofar as he himself desired to reveal himself to him through the Scriptures. What is understood in Scripture must be understood; what is not clear should be taken on faith, remembering that one hundred God is not deceitful. Faith and understanding are the only ways in which a person can relate to the creator. Luther tore faith from reason, but at the same time rejected the superintelligent, extraordinary abilities that ensure merging with the deity. As mentioned earlier, in Luther, the knowledge of God, as he is in and for himself, has received the meaning of an absolutely impossible task, and the use of reason to solve it is an irrational (seductive) action. The reformer insisted on the categorical irreconcilability of faith to reason, which justifies faith, and on the categorical irreconcilability of reason to faith, which tries to orient reason in its worldly research. The area where the mind is competent - the world and the mundane - that which the existing general religious consciousness meant as this-worldly (as opposed to the other-worldly) and as created, temporal, conditioned as opposed to the creative, eternal, absolute. The mind must deal with what is below us, not above us. For Luther, God is rather the impersonal motionless mover of Aristotle or the ruler of the Jews, but not the crucified Christ. However, the attitude towards Aristotle as a symbol of scholasticism is expressed in the main slogan of the university reform proposed by Luther - "The fight against Aristotelianism." In 1520-1522 it was in fact carried out in Wittenberg with the active participation of Luther. Aristotelian physics, psychology and metaphysics were excluded from the university course. Logic and rhetoric were preserved for those preparing for a master's degree. The reformer hoped that by excommunicating scholasticism from the universities, he would make them the center of the unrestricted study of the liberal arts, the practically useful sciences, and the new theology. However, by the end of the 1920s, it became clear that scholasticism was reborn and continued to grow. Luther's later writings, in particular his extensive "Interpretation of the First Book of Moses" (1534-1545), "are permeated with a bitter consciousness of the "indestructibility" of the scholastic style of thinking."2 Luther strongly rejected astrology, did not recognize the heliocentric hypothesis, however, there is no reason to consider him " anti-Copernican", because he did not even know the name of Copernicus, nor his teachings. Luther's reform, despite its relatively progressive features, had a class and historical character. In essence, it expressed the interests of the princes and the urban wealthy patriciate, but not the interests of the broad masses. This world is a vale of sin and suffering, salvation from which must be sought in God. The state is an instrument of the earthly world, and therefore it is marked by sin. Worldly injustice cannot be eradicated, it can only be tolerated and acknowledged, obeyed. Christians must submit to authority, not rebel against it. Luther's views supported interests requiring a strong state power. According to Karl Marx, Luther defeated slavery out of piety only by putting slavery out of conviction in its place. Martin Luther is a controversial spokesman for a turning point. The reformer manages to move forward, to the new time, even in his earliest writings. Criticism of all instances of church authority; understanding of freedom of conscience as an inalienable personal right; recognition of the independent significance of state - political relations; defense of the idea of universal education; upholding the moral significance of labor; religious consecration of business enterprise - such are the principles of Luther's teaching, which brought him closer to the early bourgeois ideology and culture. A successful continuation of the Lutheran undertakings was the Swiss Reformation by Ulrich Zwingli and John Calvin.

JEAN CALVIN

After the decline of the first wave of the Reformation (1531), a second wave rises, associated with the personality of the French theologian John Calvin (1509-1564), who spent most of his life in Switzerland. The hero of his early writings (like that of Luther) is a man disproportionate to the creator, but at the same time endowed with a sublime divine consciousness of his disproportion. Nothingness is interpreted as a quality inherent in only one divine perfection. It is absolutely unlawful for some people to look at others from a divine height, only people are equal before God. Calvin, influenced by the ideas of Luther, renounced the Catholic Church and joined the Protestant movement. In Switzerland, he wrote his main treatise "Instructions in the Christian Faith", his dogmas expressed the interests of the most daring part of the then bourgeoisie. Calvin did not put forward fundamentally new ideas, but systematized the ideas of Luther and Zwingli. Calvinism, however, further simplified the Christian cult and worship, giving the church a democratic character (the elective leadership of the church by the laity), separated it from the state, although it left it an independent political system. Calvin is on the same positions as Luther, i.e. earthly life is the path to salvation, in this life one must endure, etc. However, he emphasizes the great possibility of a Christian being actively involved in earthly affairs. Initiation to secular goods is associated with the possession of property and its multiplication; only moderate use of wealth is necessary in accordance with God's will. For Calvin, democracy is not the best way to govern; he considered oligarchy to be the most successful political system, and at least moderate democracy. Since 1536, Calvin settled in Geneva, where in 1541 he became the de facto dictator of the city, seeking to submit to the secular power of the church. The basis of Calvinism is the doctrine of divine predestination. Calvin simplified and strengthened this teaching, bringing it to absolute fatalism: some people are predestined by God to salvation and heavenly bliss even before birth, while others are predestined to death and eternal torment, and no actions of a person, nor his faith is able to correct this. A person is saved not because he believes, but because he is predestined for salvation. Divine predestination is hidden from people, and therefore every Christian must live his life as if he were predestined to salvation. Calvin preached limiting one's vital needs, renunciation of earthly pleasures, thrift, constant hard work and the improvement of professional skills. Success in professional activity is a sign of being chosen by God, the profession acts as a vocation, a place of service to God, therefore professional success is a value in itself, and not a means of achieving material wealth. Criticism of luxury and idleness turned into denial artistic creativity, literature and art, in a ban on all amusements and entertainment. Calvin reduced the freedom of conscience and interpretation of the Bible proclaimed by the Reformation to freedom from Catholicism, not allowing criticism of his teaching.

THOMAS MUNZER

As in the Middle Ages, theological rationalism during the Reformation was influenced by religious mystical teachings. The Reformation is generally connected with medieval mysticism, adopted its elements and adapted it to its own doctrine of an inner, individual relationship to God. With the most radical presentation of mysticism, we meet in the teachings of the leader of the popular revolution in Germany, Thomas Müntzer (1490-1525), a church preacher, the ideologist of the peasant-plebeian camp of the Reformation. He moved away from the petty-bourgeois limited Lutheranism, criticizing it for the fact that it deals only with questions of individual salvation and leaves the earthly order, which is considered inviolable, without attention. Müntzer saw the Reformation not so much in the renewal of the church and its teachings, but in the accomplishment of a socio-economic revolution by the forces of the peasants and the urban poor. The religious and philosophical views of Müntzer are based on the idea of the need to establish such a "God's power" on earth that would bring social equality. He, as a supporter of the idea of egalitarian communism, demanded the immediate establishment of the “kingdom of God” on earth, by which he understood nothing more than a social system in which there would no longer be any class differences, no private property, no state power. Power can be considered legitimate only when it is exercised on behalf of the masses and in their interests. According to Müntzer, God is omnipresent in all of his creations. It manifests itself, however, not as a given, but as a process that opens up to those who carry God's will in themselves. Christ is not a historical figure, but is incarnated and revealed in faith. And only in faith, without an official church, can his role as a redeemer be fulfilled. Müntzer's political program is close to utopian communism; it necessarily led to a complete divergence from Luther's petty-bourgeois reformation. Luther and Müntzer expressed different class interests, one of the burghers and princes, the other of the peasant and plebeian masses.

THE MYSTICAL TEACHINGS OF JACOB BOHME

Jacob Boehme (1575-1624) comes from a poor peasant family in Saxony, was a shoemaker. Brought up in Lutheranism, the Holy Scriptures were the source of his philosophizing. Boehme's philosophy differs from the main direction of philosophical and scientific thinking of that time: they belong neither to scholasticism, nor to the humanism and naturalism of modern times. Of his works, the most interesting are Aurora, or Dawn in Ascent, On the Three Principles, and On the Threefold Life of Man. According to Boehme, God is the highest unity, but this unity cannot be known by itself, it is inaccessible not only to human knowledge, but even God cannot know himself. The idea that the "self-discovery" of God is possible only through his transformation into nature is presented by Boehme in the terminology of the Christian doctrine of the Trinity. The thesis about the direct existence of God in things, in nature and in man is the central idea of Boehme's philosophical and theological system. Nature is closed in God as the highest and active first principle. God is not only in nature, but also above it. Man is both a “microcosm” and a “little god”, in which everything worldly and divine takes place in all its complex inconsistency. It acts as a unity of the divine and natural, corporal and spiritual, evil and good. Boehme's mysticism finds its successors in the mystical currents of the 17th and 18th centuries, and his dialectics in German classical philosophy Schelling and Hegel.

COUNTER-REFORMATION

The Protestant Reformation resonated with Catholicism. Since the 40s of the 16th century, Catholics have been fighting for the return of lost positions; in Western Europe begins the period of the counter-reformation. The participants in the movement sharply raise the question of strengthening unity in the very organization of the Catholic Church, of strengthening internal discipline and papal centralization, but the main thing was the open struggle of Catholicism against Protestantism. The order - "The Society of Jesus" (Jesuits) - founded by the Spaniard Ignatius of Loyola in 1534 and approved by the pope in 1540, became the advanced combat detachment of Catholics. The Jesuits formed the core of the Inquisition, reorganized to fight the Reformation. The Inquisition arose as a manifestation and consequence of the crisis of church authority and ideology: it was necessary to bring church ideology into line with the new social situation and the new ideological currents of the era. The Council of Trent (1545-1563), however, shied away from solving philosophical problems and disputes between schools, not wanting to disturb the unity of the church. During this period, there is a new revival of scholastic philosophy in the form of Thomism. First it was in Italy, then in Spain, initially the Dominicans played the main role, then the Jesuits. Highest value for attempts to restore medieval scholasticism in this era had the teachings of the Spanish Jesuit Francis Suarez (1548-1617).

The book Societies... discussed the development of cultural innovation in the small "hotbed" societies of ancient Israel and Greece. The analysis focused on the conditions under which meaningful cultural innovation could take place and, over time, break away from its original social roots. These two models were chosen because of their decisive contribution to subsequent social evolution. Elements originating in "classical" Jewish and Greek origins, having undergone fundamental changes and mutual combinations, constituted the majority of the main cultural components of modern society. Christianity was their core. As a cultural system, it ultimately proved its ability to both absorb the most significant components of the secular culture of antiquity and create a matrix from which new foundations of secular culture could stand out.

Christian culture, including its secular components, was able to establish a clearer and more consistent differentiation from the social systems with which it was in a relationship of interdependence than any of its predecessors could. Due to this separation from society Christian culture was able to act as a more effective and innovative force in the development of the entire socio-cultural system than other cultural complexes that appeared before it.

No cultural system, however, is institutionalized by itself; to do this, it must be integrated with the social environment that ensures the satisfaction of the functional needs of a real society (or several societies). Evolution involves continuous interaction between cultural and social systems, as well as between their respective components and subsystems. Social

The real prerequisites for the effectiveness of culture thus not only change, but at each stage may depend on the previous stages of the institutionalization of cultural elements.

In this regard, the Roman Empire is of particular importance for our analysis. First, it was the main social environment in which Christianity developed. Because Roman society owed so much to Greek civilization, Greek influence entered the modern system not only in a "cultural" way, through Christian theology and the secular culture of the Renaissance, but also through the structure of Roman society, especially in the eastern part of the empire, where the educated classes remained Hellenized after Roman conquest. Second, the legacy of Roman institutions was incorporated into the foundations of the modern world. The extremely important point is that the Greek cultural and Roman institutional heritages affected the same structures. The legal order of the empire turned out to be an indispensable condition for Christian proselytism, as a result of which there was a combination of patterns, which was reflected in the fact that elements of Roman law entered both the canon law of the church and the secular laws of medieval society and its successors.

We begin our analysis with sketches relating to the two main social "bridges" between ancient and modern worlds- Christianity and some institutions of the Roman Empire. Then, skipping a few centuries, consider the more immediate predecessors of modern society - the feudal society with its culmination in the late Middle Ages, then the Renaissance and the Reformation.

EARLY CHRISTIANITY

Christianity originated as a sectarian movement within Palestinian Judaism. Soon, however, it broke with its religious-ethnic community. The decisive event in this process was the decision of the Apostle Paul, according to which a non-Jew could become a Christian without becoming a member of the Jewish community and observing the Jewish law 1 . Thus the early Christian church became an association-type religious community, independent of any naturally defined ascriptive-type communities, whether ethnic or

1 Nock A D St Paul NY Harper, 1938

territorial. It centered around a purely religious task - the salvation of the soul of each individual person - and in this respect it was especially different from any secular social organization. Through the proselytizing activities of the apostles and other missionaries, the Christian church gradually spread throughout the Roman Empire. In the early stages, it enjoyed success mainly among the poorer sections of the urban population - among artisans, small traders, etc., who were free from both peasant traditionalism and the interest in the status quo inherent in the upper classes 2 .

From the point of view of religious content, the most important elements of continuity from Judaism were transcendental monotheism and the idea of a contract with God. Thus, the spirit of “chosenness” by God for the fulfillment of a special God-given mission was preserved. In classical Judaism, this status was given to the people of Israel; in Christianity, it was assigned to all individuals professing the faith, through faith gaining access to eternal life 3 . Salvation could be found in the church and through the church, especially after the institution of the holy sacraments was established. early church was a voluntary association, as a sociological type completely opposite to such a community as "the people". One could be a Jew only as a total social personality, one of the "people"; in Christianity, at the level of participation in society, a person could be both a Christian and a Roman or an Athenian, a member of a church and an ethno-territorial community. This step was crucial for the differentiation of both role and team structures.

This new definition of the foundations of the religious community and its relationship to secular society required theological legitimization. The new theological element was Christ, who was not just another prophet or messiah of the Jewish tradition - these figures were purely human, with no claims to divinity. Christ was both man and God, the “consubstantial son” of God the Father, but also a man in flesh and blood. In this dual nature of his, he appeared to bring salvation to mankind.

The transcendence of God the Father was the main source of the sharp division between what was later called "spiritual" and "secular". Serve as the basis for their integration -

2 Harnack A. The mission and expansion of Christianity. N.Y.: Harper, 1961.

3 Bultmann R, Primitive Christianity. Cleveland: Meridian, 1956.

whether the relationship between human souls and God through and "in" Christ and his church, which is theologically defined as the "mystical body of Christ" and participates in the divinity of Christ through the Spirit of God 4 . Christ not only brought salvation to souls, but also freed the religious community from its former territorial and ethnic ties.

The relationship between the three persons of the Holy Trinity and each of them to man and other aspects of being is extremely complex. A stable theological ordering of these relations required intellectual resources that were absent in prophetic Judaism. It was in this direction that late Greek culture played a decisive role. Christian theologians in the 3rd century n. e. (especially the Alexandrian fathers Origen and Clement) mobilized the sophisticated means of Neoplatonic philosophy to solve these complex intellectual problems, 5 thereby creating a precedent for convergence with secular culture, which was not available to other religious movements, in particular Islam.

The notion of the Christian church as both a divine and a human institution had a theological origin. The idea of it as a voluntary association with significant signs of egalitarianism and corporate independence in relation to the social environment was largely formed on the basis of the institutional models of antiquity. A striking symbol was the use of St. Augustine of the word "hail" in a meaning close to the word "polis" 6 . To be sure, the church was an association of religious "citizens" like a polis, especially as far as local congregations were concerned. Just as an empire can be thought of as city-states, so the Church created a model for it as the growing movement needed power structures to stabilize relations between its local congregations. A certain centralization was also necessary, which was gradually carried out in the establishment of the Roman papacy. Although the church institutionally differentiated from all secular organizations, at the same time structurally it became more in line with the social reality surrounding it.

4 Neck A.D. Early Gentile Christianity and its Hellenistic background. N.Y.: Harper, 1964.

1 Jaeger W. Early Christianity and Greek Paideia. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard Univ. Press, 1961.

Cochrane Ch.N. Christianity and classical culture. N.Y.: Oxford Univ. Press. 1957.

An important feature of the differentiation of the Christian church from secular society was the clarity and sharpness of the boundaries drawn: the early Christian lived "in the world", but was "not of this world." The large society was pagan and seemed to the Christian to be completely devalued, the kingdom of unredeemed sin. The famous injunction "Caesar - Caesar" had to be understood as a recognition that Caesar is a pagan monarch, a symbol of a pagan political and social order. The fact that the “acceptance” of Roman power was expressed here showed Christian passivity in relation to everything worldly. As E. Troeltsch emphatically insisted, early Christianity was not a social reform movement or a revolutionary movement. Recognition of the authority of Caesar in no way meant positive integration, for it was rooted in the eschatological expectations of the imminent second coming, the end of the world and Doomsday 7 .

Christian movement as a whole was initially ambivalent in its relation to the secular world, which again was largely inherited from Judaism. On the one hand, it affirmed the priority of "eternal life" over all worldly affairs. Therefore, along with proselytism, it emphasized such means of salvation as personal piety and asceticism. On the other hand, Christ and his church, like the people of Israel, had a God-ordained mission on this earth, which actually meant a mission in human society. And although the position of the church in imperial society was forced to push this component into the background, its evolutionary potential was very significant.

Christian detachment from worldly affairs faced more and more serious problems with the conversion to the Christian faith of large sections of the population, and especially representatives of the higher, socially and politically more responsible classes 8 . This process reached its climax at the beginning of the 4th century. n. e. with the proclamation of a new imperial religious policy, which was reflected in the Edict of Milan (announcing tolerance for Christianity), in the conversion of Emperor Constantine to Christianity and in the declaration of Christianity as the state religion 9 .

1 Troeltsch E. The social teachings of the Christian Churches. Vol. 1. N.Y Harper, 1960. s Ibid. 4 Lietzinann H. A history of the early Church. Cleveland: Meridian, 1961. Vols 2. 3

This culmination was not only a great triumph, but also a source of great tension within Christianity, as the church was in danger of losing its independence and becoming an instrument of secular political power. It is significant that it was during this period that the monastery was established 10 . The apostle Paul's command to "remain in the position in which you were called" seemed from the very beginning not radical enough to a certain minority of Christians who completely broke with the world and became hermits. Now, however, such sentiments led to the creation of organized communities of believers who completely dedicated their lives to religion and left the world, taking a vow of non-possession, celibacy and obedience 11 .

Although Christianity was a "hotbed" movement with potential for the future social development, it could not transform the Roman Empire, because there were no necessary conditions for its institutionalization. The monastic movement, on the other hand, formed another, special kind of “seedling nursery” already within Christianity and became a powerful and ever-increasing evolutionary lever of influence both on the “secular” church and on secular society.

Institutional structuring of the Christian mission in a world in which monasteries played everywhere important role, turned out to be closely connected with the process of differentiation of the eastern and western branches of the church. Partly as a result of the weakening of secular power in the West, including the loss of the status of the imperial capital by Rome, the church was given great opportunities there to become an independent "actor of action." Acting as a single organization of all Christians, laity and clergy, the Western Church created a "universal" episcopal system, centralized under the auspices of the papacy in Rome 12 . During the "Dark Ages" and throughout most of the later Middle Ages, this organization proved to be more effective than any of the secular ones, and this was due to the long-term influence of three important points in the development of the church.

Firstly, largely under the influence of Augustine, at the highest theological level, beyond the "city of men"

Tufari P. Authority and affection in the ascetics status group: St. Basilic definition of monasticism/Unpubl. dissert. Harvard University.

"" Workman H.B. The evolution of the monastic ideal. Boston. 1962.) ~ Lietmann H. Op. cit. Vol. four.

an almost legitimate place, despite the fact that a distinction was made between it and the "city of God." In contrast to the total alienation from worldly society I, characteristic of early Christianity, Augustine's concept affirmed the idea of "negative tolerance" towards him and allowed the possibility of his moral improvement under Christian influence. as a completely legitimate aspiration 13 . Augustine also went much further than his predecessors in embracing the secular culture of the ancient world.

Secondly, with the establishment of the Benedictine order, Western monasticism began to pay much more attention to worldly affairs than Eastern monasticism. Interest in the secular world was strengthened with the appearance in the Western Church of other orders, such as the Cluniac monks, the Dominicans, the Franciscans, and finally the Jesuits.

Third, the organization of the church was cemented through the sacraments, which took their final form before the beginning of the Middle Ages. The priestly rank has become a position independent of the personal qualities of the persons who occupy it, and, consequently, of their particularist ties 14 . The Western Church has achieved a much higher level of "bureaucratic" independence of its white clergy than the Eastern Church, where bishops are required to come from monks and parish priests are closely involved in the life of local communities.

INSTITUTIONAL HERITAGE OF ROME

It is well known what a sharp decline the Roman Empire experienced when it reached the highest level of civilization. Especially this decline was expressed in the disintegration of political power; in the West and in the emergence in its place of many changing tribal and regional groups and authorities. These changes were accompanied by the virtual disappearance of the money market economy and a return to local self-sufficiency and barter 15 .

n Cochrane C /7. N. Op. cit; Troeltsch E. Op. cit.

14 Weber M. The Sociology of religion Boston: Beacon, 1963. Society image. M.: Lawyer, 1994.J

b Moss H.St.L B. The birth of the Middle Ages. L.: Oxford Univ. Press, 1935: Lot F. The end of the Ancient World and the beginning of the Middle Ages. N. Y. Harper, 1961.

When the gradual revival and consolidation began again, between the church and secular power an important new relationship emerged. The legitimization of Charlemagne's regime depended on its relationship with the Church, which found symbolic expression in his coronation by Pope Leo III in 800 AD. e. This ceremony served as a model for the entire Holy Roman Empire, which, although never a highly integrated political system, nevertheless served as a legitimizing basis for a unified Christian secular society 16 .

Within these institutional frameworks, the great medieval "synthesis" looked like a differentiation of church and state, the latter in the specifically medieval sense of the term. This differentiation was defined as the separation of the spiritual and secular "tools" of the Christian mission. As a result of this special way of differentiation and integration, the core of what E. Troeltsch called the first version of the idea of a Christian society 17 was formed. The main institutional elements of Roman origin that survived the Middle Ages were thus closely connected with the development of the church.

During the period of the migration of peoples, the universalist structures of Roman law were severely undermined due to the “personalization” of law, when a person began to be judged according to the law of his tribe 18. This particularistic reference to tribal affiliation could only be overcome in jurisdiction and law enforcement by a gradual revival of the territorial principle, for this side of the law is directly related to the status of territorial political power. Although it was recognized that the civil law of the newly formed empire was Roman law, the empire was too loose to serve as an effective subject for the detailed development of the law and its implementation. So the legal tradition was limited to exerting a kind of “cultural pressure” in the form of a legitimizing influence on the process of establishing territorial laws that did not cover the entire empire 19 .

Yet it has hardly been questioned that law as such meant Roman law, and that the legal system of imperial Rome remained valid even in English common law, which was not so much a new legal system as an adaptation.

"" Pirenne H. A history of Europe. 2 vols. garden city; N.Y.: Anchor, 1958.

Troeltsch E. Op. cit. Vol. 1.

Mcllwam C.H. The growth of political thought in the West. N.Y.: MacmiUan, 1932.

"Ibid; Gierke 0. van. Political theories of the Middle Ages. Boston: Beacon, 1958.

tion of Roman law to the conditions of England 20 . Moreover, the Church adapted a large part of Roman law in the form of canon law to regulate its own affairs and created within the clergy a special rank of legal experts. It is even possible that the "bureaucratization" of the medieval church was of less importance than its ordering by means of a universalist legal system.

The rigid territorial attachment of political institutions is the second essential component of modern societies, the existence of which, more than any other source, they owe to the Roman heritage. Despite the many differences between Roman and modern state institutions, the Roman heritage and the Roman model served as the most important starting point for the development of the early modern European state, not least through the legitimization inherent in the ideas of the continuity of the state organization 21 .

The third main component of the institutional heritage of antiquity was the principle and model of the "municipal" organization. The Roman municipium originated from more ancient city-states - the Greek polis and the cities of Rome and other Italic provinces. The Municipium lost its political independence long ago, but retained many of its old institutional arrangements. The most important of these was the idea of its structural core in the form of a corporation of citizens. In certain fundamental respects, the citizens of the municipium were a body of equals, having the same legal and political rights, and bearing the same military and other similar duties of citizens. Although in all the municipia, as in Rome, gradually aristocracies of rich and noble citizens arose who monopolized public offices, they still retained, in contrast to rural society, especially the period of feudalism, the spirit of association. The survival of such urban communities was an important feature of pre-modern Europe when compared with any other Oriental society at about the same stage of development.

20 Maitland F.W. The constitutional history of England. Cambridge (Eng.): Cambridge Univ. Press, 1908.

21 Morrall l.B. Political thought in Mediaeval Times. N.Y.: Harper. 1962

22 Weber M. The city. N. Y.: Free Press, 1958. [Weber M. City // Weber M. Selected. Society image. M.: Jurist, 1994.)

MEDIEVAL SOCIETY

The fact that the period of development and transition from the end of the Middle Ages to the first new formations of a society that embarked on the path of modernization was long and uneven is largely due to the fact that in medieval society features that favored this process were whimsically combined with those that were basically incompatible with modernity and became hotbeds of resistance to the transition to it. Considered as a "type" of a societal structure, feudal society is sharply opposed to more developed types - both those that preceded it and those that came to replace it. It was characterized by a radical retreat from almost all elements of the developed Roman society to more archaic forms. However, as soon as the point of maximum regression was reached, recovery and dynamic progress began quickly. The key point in this development was that feudalism - the product of a backward movement - received only a secondary legitimization. Although the loyalty of the feudal type was undoubtedly romanticized and received, in fact, the blessing of the church, this recognition was conditional and limited. On the whole, they turned out to be quite easily vulnerable to other claims that could appear both earlier and later than them and which were deeply rooted in a culture with rather highly rationalized key components.

Starting from the XI century. elements began to assert themselves in society that could give rise to primary legitimation, initiating a process of differentiation and related changes that eventually led to the creation of a modern structural type. The general direction of this evolution was determined by achievements within the framework of the “structural bridges” already mentioned above: this is the main orientation of Western Christianity, the relative functional isolation of the organizational structure of the church, the territorial principle of political allegiance, the high status of the Roman legal system and the principle of association underlying urban communities.

The fragmentation of the social organization of the Roman Empire gradually led to the creation of a highly decentralized, localized and non-structurally differentiated type of society commonly referred to as "feudalism" 23 . General ten-

"h The most authoritative and useful for sociological analysis, an all-encompassing source can be the book of M. Block: Block M Feudal society. Chicago, - Block M. Feudal society // Block M. Apology of history. M .: Nauka, 1973.

The trend of feudal development was the destruction of the universalist basis of order and its replacement by particularistic ties, originally "tribal" or local in nature. Along the way, the old elements of relative equality of individual members of associations gave way, at least at the level of basic political and legal rights, to blurred hierarchical relationships based on the inequality of mutual obligations of vassalage, patronage and service.

Feudal hierarchical relations began as "contractual", when the vassal, giving an oath of allegiance, agreed to serve the master in exchange for his patronage and other privileges 24 . In practice, however, they quickly became hereditary, so that only if the vassal did not have a legitimate heir, his master could freely dispose of his fief and appoint a “new person” as his successor. For peasants

the feudal system established hereditary lack of freedom in the form of the institution of serfdom. Full recognition of the legitimate heredity of the status was, however, one of the signs

aristocracy.

Probably the most pressing day-to-day issue at the time was providing simple physical security. The disorder generated by the "barbarian" invasion continued further due to constant raids (for example, Muslims - in the east and south, Huns - in the east and north, Scandinavians - in the north and west) and continuous civil strife as a result of political fragmentation 25 . Therefore, the military function was predominantly developed, and military means of resisting violence became the basis of security. Based on the powerful traditions of antiquity, a military estate rose in secular society, securing its position through the hierarchical institution of vassal dependence.

However, as time went on, the ability to maintain simple and clear hierarchical relationships became more and more problematic. They became so intricate that many people exercised their feudal rights and obligations within several potentially hostile hierarchies at once. Although the fief relationship, which was considered paramount in relation to all other obligations, was an attempt to solve this problem, nevertheless, rather, they were a sign that

-* Ganshoff F.L. Feudalism. N.Y.: Harper, 1961. 2-Ibid. Part I.

the institution of royal power was not completely feudalized and gradually restored its supremacy 26 .

After the 11th century the territorial organization of the state, closely connected with the monarchical principle, began to steadily gain strength, although not everywhere in the same way. In Europe, population density gradually increased, economic organization grew, physical security increased, all this as a whole led to a shift in the principles of balance from feudal organizational dependence of vassals (with its very fragile balance) to territorial. Along the way, there was an important crystallization of the institution of the aristocracy, which can be seen as a "compromise" between the feudal and territorial principles of organization 27 . In its fully developed forms, the aristocracy was a phenomenon late Middle Ages. At the macro-social level, it represented the focal point of the two-class system from which the modern type of secular social stratification of the nation-state developed.

A sharp economic decline was closely intertwined with the political feudalization of the early Middle Ages. The resource base of society became more and more agrarian, acquiring a relatively stable form of organization in the form of the institution of feudal land tenure. The estate was a relatively self-sufficient agricultural economy with a hereditary labor force assigned to it, dependent in its legalized status of “non-freedom” on the feudal lord, usually some individual, but often some kind of church corporation - a monastery or a cathedral chapter. The functional vagueness of the estate was reflected in the status of "landowner, who combined the roles of landowner, political leader, military leader, judge and organizer of economic life 28. Such vagueness fully corresponded to the manorial estate as the center of guaranteed security in the midst of feudal chaos, but prevented it from becoming an organization facilitating local modernization, a type of organization that cities were much closer to.

It can be argued that in broad sense the social structure of the church was the main institutional bridge between ancient and modern (modernized) Western society.

16 Block M. Op. cit. 27 Ibid.

Ibid. Part V; Pirenne H. Economic and social history of Medieval Europe. N. Y.: Harvest, 1937. Part Sh.

pom. But in order to effectively influence evolution, the church had to connect with secular structures at some strategically important points. M. Weber insisted that one of these strategic points was the European urban community 29 . As far as church membership is concerned, social divisions within the urban communities were to a certain extent muted, though not entirely eliminated. First of all, this was expressed in the fact that all members of the urban community, without any distinction, were given access to the mass 30 .

The nature of the religious component in the city organization was most clearly demonstrated by the cathedral, which was not just a building, but an institution that combined two levels of church organization - the seat of diocesan authority and the center of the cathedral chapter, which is an important collegiate element of the church structure 31. The very significant participation of the guilds in the financing of chapters and the construction of temples indicates that the religious organization was closely connected with the economic and political life of the cities that were gaining strength.

The most important phenomenon in the development of secular-type associations in cities was the emergence of an urban version of the aristocracy in the form of a patriciate - the highest stratum of citizens organized into a corporate entity. The distinctive feature of these groups lay in the very principle of their organization, which was the opposite of the feudal principle of hierarchy 32 . They were organized in guilds, among which the most prominent and influential place was occupied by the guilds of merchants. But each individual guild itself, following the pattern of the polis or municipium, was basically an association of equals. Although within the same urban community there were guilds that were

29 Weber M . The city.

4 In the countryside, the usual order was that the master of the estate went to mass in his chapel, and the common people went to the village church or to the temples of a nearby monastery or city, if they attended worship at all. Every more or less noble person had his own confessor. In this regard, it is noteworthy that Thomas Aquinas argued that the urban way of life was more suitable than the rural one for the cultivation of Christian virtue. See: Troehsch E. Op. cit. Vol. 2. P. 255.

Southern R W. The making of the Middle Ages. New Haven: Yale Univ Press, 1953. P. 193-204.

32 Block M. Op. cit. P. 416.

j3 Pirenne H. Early democracies in the low countries. N. Y.: Harper, 1963.

at different levels of prestige and power, occupying unequal positions in the political structure of the city, and although the cities themselves could occupy a different place in the broader political structures of feudal society, nevertheless, urban communities were an example of organization, the opposite of feudalism and consonant with the main direction of future development 34 .

Probably the most important evolutionary events of the early Middle Ages took place in the church, the only structure sufficiently comprehensive to influence institutional arrangements throughout Europe. The turning point came perhaps at the end of the 11th century, during the papacy of Gregory VII. By that time, the church had already renewed interest in broad philosophical and theological topics related to the establishment of a purely Christian body of knowledge, which could serve as a guide on the path to the creation of a Christian society 35 . Looming on the horizon was the creation of the first great scholastic synthesis. A systematic study of canon law and secular Roman law had already begun, and Pope Gregory VII supported these initiatives. At the level of the social structure, however, the decisive moment was, in all likelihood, Gregory's insistence that religious discipline in the church as a whole approach that of the monastery, combined with the defense of the interests of the church in the world 36 . He and some of his successors raised the power of the church and its structural independence to such heights that opponents of such a position spoke of the predominance of the church over secular structures. Such dominance was unimaginable in the Byzantine Empire.

In some respects, Gregory VII's main innovation was his demand for celibacy for the white clergy? one . While in the feudal system the more "personal" principle of feudal fidelity was rapidly being replaced by the principle of heredity, it decisively removed the clergy and especially the episcopate from the latter's sphere of action. Whatever the morality of the white clergy in the field of sexual relations, the priests could not have legitimate heirs, and their parishes and positions were not

h Pirenne H. Mediaeval cities. Princeton: Prmceton Univ. Press, 1925. Ch.2 "Municipal institutions".

ъ Southern R. W. Op. cit.; Troeltsch E. Op. cit. * Man-all J B. Op. cit.

"Lea H C. History of Sacerdotal Celibacv in the Christian Church. N Y .: Macmil-lan. 1907.

became an institutionalized hereditary function, as happened with the institutions of the monarchy and the aristocracy. This position could not be destroyed even by the fact that, according to common practice, the higher clergy were appointed from among the aristocrats. Although clergy, bishops, and, in general, popes have been chosen for many centuries largely on the basis of their ancestral ties, attempts to legitimize such an order have been largely rejected, while in many secular contexts the principle of heredity has become increasingly ingrained. The state of tension between the spiritual universalism of the church and the feudal secular particularism, which manifested itself in organizations of both the religious and secular types, served as a powerful counteract against the slipping of Western society into comfortable traditionalism.

DIFFERENTIATION OF THE EUROPEAN SYSTEM

Until now, we have been talking about feudal society in terms of its constituent structures, regardless of their differentiated distribution over various geographical areas of the European system. Now let us dwell on the extent to which the current differentiation of Europe as a system was anticipated in the periods preceding the beginning of modernization, and for this we will consider how the various institutional components were distributed throughout Europe 38 .

The social environment of the European system was made up of its relations with neighboring societies, which differed greatly depending on their geographical location 39 . The social environment in the northwest of Europe was not problematic, since this region bordered on the Atlantic, which at that time did not represent a zone of any significant social and political interchange. In the south and east, however, the social environment was extremely important. Spain throughout the

38 A clear description of this distribution can be found in M. Blok's work cited here. In his approach, for the first time, the idea was indicated that such a differentiated distribution, with certain reservations about subsequent changes in the course of development, can be attributed to times far preceding the first major stages in the development of the modern system, as they are treated in subsequent chapters of this book,

"See: Halecki O. The limits and divisions of European history. Notre Dame (Ind.)" Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 1962. Heileske describes the general evolutionary deg of sociogeographical differentiation in Europe.

the non-century period was partially occupied by the Moors, and for the eastern Mediterranean in that period, relations with the Saracens were of decisive importance. To the south-east lay the Byzantine Empire, which by the end of the Middle Ages fell into the hands of the Turks, and to the north-east was the region of the spread of Orthodox Christianity, which eventually took shape in Russia. The eastern frontier was a zone of struggle and an equilibrium that fluctuated along religious and ethnic lines. Poles, Czechs and Croats became mostly Roman Catholics, while Russians and most of the South Slavs converted to Orthodoxy. At the same time, from Austria, further north, there was an unstable border between the Germanic and Slavic peoples, which did not coincide with the religious demarcation. The strategic enclave immediately to the east of the area of German settlement was the Hungarian ethnic group - a fragment of the Hun invasion.

Thus, between the eastern and western borders of Europe there was a huge difference regarding the social environment of these places - both in terms of physical and geographical features, and in the degree of previous penetration of Roman influence, and in the consequences of the split of the western and eastern churches. There were also major differences between north and south, engendered by the presence of a physical barrier in the form of the Alps and the Pyrenees. Italy was the location of the control center Roman Catholic Church, but never - the capital of the Holy Roman Empire. Although Latin culture, primarily through the language, penetrated into Spain, France and some other border regions, the main ethnic composition of the transalpine societies was not Latin.

Italy played a special role in the formation of medieval society for two main reasons. Firstly, there was an ecclesiastical altar in it and, consequently, the influence of the church was exercised in the most concentrated form. Secondly, Roman institutions were most firmly rooted here, which were able to recover faster after a minimal period of development of feudalism.

In the conditions of the Middle Ages, the church was intertwined economically and politically with secular society, of course, much more closely than in the modern era. Especially important aspect The involvement of the church in worldly affairs was the direct state jurisdiction of the popes over the territory, which received the name of the Papal States. At the same time, the general decentralization of medieval society meant that the urban component of Roman

heritage most strongly manifested in Italy. To the north of Rome, the city-state became the dominant organizational form in Italy. The upper classes of northern urban communities have become a kind of amalgam of rural-rooted originally feudal aristocracies and urban "patriciates". And yet they were the upper classes of the urban type; even if their members owned almost all agricultural land, they were decidedly different from the feudal aristocracy of the North 411 . Such conditions strongly prevented the emergence, at first, of a predominantly feudal structure, and later of territorial states that, in terms of the scale of their political structure, went beyond what could be controlled by a single urban center. Since the widespread use of Roman law in secular society depended on the development of territorial states, it did not flourish here until very late times. Like their ancient counterparts, the city-states of antiquity, the Italian cities were unable to defend their political integrity in the system of "great powers". Nevertheless, Italy at that stage was, perhaps, for European society the main subsystem for the preservation and reproduction of the model, the main hotbed of subsequent changes in both secular and ecclesiastical culture 41 .

The eastern borderlands were on the whole the most feudalized part of the European system, although here, especially in Germany, original and very diverse forms of organization 42 developed. East of the Rhine Valley and northeast of the Baltic Sea, the urban component gradually weakened, dropping to the lowest level in Europe. The economic and cultural conditions here were certainly more primitive than in other regions, and the proximity of the border made it necessary to emphasize military pursuits. The feudal structure and social stratification are generally more rigidly hierarchical than in the western regions, which created the basis for more authoritarian regimes. Hierarchical differentiation and political power thus took precedence over economics and culture. The resulting hierarchical political centralization created the conditions for a kind of accumulation of resources for political efficiency, which had important implications for the future of the entire European system.

411 See: Schevill F. The Medici. N.Y.: Harcourt, 1949.

41 Plumb J.H. The Italian Renaissance. N.Y.: Harper, 1965. Ch. ten.

42 Bloch M. Op. cit.

Topics. It can be said that the eastern border areas played the role of an adaptive subsystem in the European system, as they created organizational forms to protect it from sociopolitical threats, and after them, cultural ones.

The ground from which the most important social and political innovations emerged was mainly in the northwest of Europe. The significance of Paris as a center of scholastic philosophy and of the universities at Oxford and Cambridge was that both were cultural innovations. The same geographic area provided two particularly valuable social innovations. First, England and France provided the earliest examples of non-feudal territorial states, although there was also a feudal underpinning in their development. Secondly, here, in the north-west of the empire, urban communities flourished, which were concentrated mainly along the Rhine valley - from Switzerland to the North Sea.

All this happened largely because of the organizational looseness of the empire. Due to the peripheral position of England and France, their kings could from early times ignore their subordination to the emperor. In addition, many urban communities on the continent became "free cities" of the empire, gaining substantial freedoms from feudal structures and emerging territorial monarchies. Since these cities were usually also the location cathedrals, their position was strengthened by an alliance with the church.

These processes, which initially centered on England and France, constituted the first stage of differentiation on the way to the formation of the modern form of the societal community. The development of free cities, in many respects parallel to the development of cities in Italy, served as an impetus for further differentiation of the economy from political structures and from the societal community as such.

None of these forms of structural differentiation was compatible with the generally prevailing feudal organization. The very first kings of territorial states were both kings in the later sense of the word and feudal magnates; theoretically, they were the most noble vassals of the Holy Roman Emperor, while their "barons" were in turn and mainly their feudal vassals. The feudal estates did not just administer

"Petit-Dutaillis Ch. The feudal monarchy in England and France. L.: Routledge. 1936. Even today, Hamburg and Bremen have the status of free cities.

power in their fiefs, but formed the core of a societal community; they were, as it were, ex officio, representing the most prestigious stratum, at the same time being a symbolic focus of social solidarity. The network of feudal ties that radiated from them formed the basis of the social structure. The "lower classes" were woven into this network through their unfree status within the estate, directly belonging only to their master and no one else. Virtually no civil administration reached the level of the owner of the manor, not to mention his serfs. One of the first exceptions to these rules was the king's prerogative to keep "peace", most fully embodied in the English judicial system, through which the king could intervene in local affairs in case of serious crimes or quarrels between two feudal lords. With the development of feudalism, vassal relations became more and more ramified, and this led to the further spread of royal intervention and contributed to "national" integration 46 .

The system of feudal barony gradually transformed into what became the aristocracy of early modern societies. Politically, perhaps the most decisive innovation was the appropriation by the royal governments of two closely related prerogatives - firstly, to have military units independent of the feudal contingents, subordinate primarily to the barons, and, secondly, to establish a direct taxation, bypassing feudal intermediaries. The successors of the barony system nevertheless remained the "social" class with the most prestigious status, directly linked to the monarchy in the sense that the king was always the "first gentleman" of the state and head of the aristocracy. As a result of these changes, landed property began to break away from the status of landowner, which assumed political power not only over land, but also over people, but at the same time it remained the main economic base of the aristocracy.

Where there were not enough forces to establish state administration over large territories, it happened that cities became completely independent. In addition to being the site of a tradition of political independence that prevented the advance of absolutism, the Free City zone

45 Maitland F. W. Op. cit. 4(1 Block M. Op. cit.

also had all the conditions for the consolidation of an independent social stratum, the main leadership group, alternative to the aristocracy - the bourgeoisie 47 . The economic base of this group was concentrated not in land ownership, but in trade and finance. Although the guilds of artisans also occupied a prominent place in the urban structure, the trade guilds, especially in the most significant cities, usually had more influence.

On both sides of the Alps, cities became the main centers of the emerging market economy; probably the most significant factor in this was their independence both from the newly formed monarchies in England and France, and from the dominance of the empire. Within the larger system, the independent position of a group of Rhine towns could not but strengthen the positions of their brethren in England and France. Under certain circumstances, and especially in capital cities, alliances arose between kings and the bourgeoisie, which constituted an important counterbalance to the landed aristocracy. This is especially characteristic of the post-feudal period.

Under the conditions of relative isolation and the strong power established on the island after the Norman conquest, England achieved a degree of political centralization higher than on the Continent. At the same time, she did not follow the path of development of royal absolutism due to the solidarity of the new aristocracy, which consisted of close associates of William the Conqueror. In less than a century and a half, the barons were capable of sufficiently united corporate action to impose the Magna Carta on their king. This corporate solidarity was in turn linked to the conditions that favored the formation of a parliament. All this led to the fact that the English aristocracy moved further and faster than any other from its feudal principles, thereby gaining especially significant positions of power and influence in the emerging state.

Compared with Flanders and some other areas of the continent, England long remained economically backward. However, the English political structure provided fertile ground for future economic development, since the power of the landed aristocracy in opposition to royal power created a situation of tertius gaudens for the merchants. So

4 Pirenne H. Early democracies in the low countries. w Mankind F.V.V. Op. cit.

Thus, in England, the ingredients for the future synthesis of all changes directed towards differentiation were implicitly maturing.

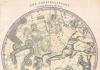

RENAISSANCE AND REFORMATION

The Renaissance marked the beginning of a highly developed secular culture that emerged from the previously common religious matrix. The birthplace of the Renaissance was Italy, it was here that the birth of modern arts and intellectual disciplines, including the related field of legal culture, took place. Indeed, even theology itself experienced the backlash of new elements of secular culture, which later crystallized in the form of philosophy.

The cultural components that made up the culture of the Renaissance had their historical roots not only in the depths of the Middle Ages, but even further - in antiquity. Ancient culture itself, however, did not reach the same level of differentiation, as it remained religious in a certain sense, which was not characteristic of Western culture after the Middle Ages. Scholastic philosophy, the most important integral component of a rationalized medieval culture, did not hide its classical roots, especially evident in the appeal of the Thomists to Aristotle, was closely tied to the theological system of thought and did not have the cultural autonomy characteristic of post-Renaissance thought 49 .

The Church at the beginning of its formation took, and then developed extremely important elements classical culture. The era of the Renaissance was marked by a gigantic advance of this heritage, mainly in the direction of its secularization. In accordance with our analytical scheme, this process can be defined as differentiation, but since it left the possibility for the perception of elements that in the previous, less differentiated cultural system turned out to be "indigestible", it was also a process of inclusion.

A distinctive feature of this process is that it took place within a religious framework 50 . The church and the aristocracy were the most important patrons of the new art, mostly devoted to religious subjects and the decoration of the temple.

49 Tmelrsch E. Op. cit. Vol. 2; Mcllwain S. H. Op. cit. 30 Tmeltsch E. Op. cit. Vol. 2.

mov, monasteries and other religious buildings. However, artists, and later scientists, were more and more often recruited from secular, rather than from spiritual circles, and in developing the consciousness of their corporate affiliation and autonomy (as masters of their craft), they went far from the builders and decorators of medieval cathedrals 51 . Universities were not yet particularly prominent, except in certain areas, such as law. Nevertheless, gigantic steps were taken during this period regarding the withdrawal from the tutelage of the church of the role-playing activity of any more or less professional specialist in cultural affairs. Although some of the ideas of the late Renaissance penetrated the Protestant regions only after the Reformation, they, too, were not openly anti-religious, but were perceived and disseminated within the framework of religion.

The Renaissance appears to have begun with a revival of literary styles and interest in Latin antiquity, especially in the secular writings of the humanists 52 . The subjects and themes brought back to life immediately had a tremendous impact on the visual and plastic arts - architecture, painting, sculpture. Science only later reached a comparable level of perfection, as a result of processes of both internal differentiation and the more general differentiation of secular culture from the social matrix. For example, Leonardo was a master in both the artistic and scientific fields, while Raphael was not a scientist, and G. Galilei was a painter. This differentiation, in all likelihood, formed the basis of many manifestations of modern culture, since the new science, which reached its culmination in the 17th century. in the person of I. Newton, became the starting point for the first great wave modern philosophy. This philosophy, in turn, served as the immediate foundation for the development of a complex of secular knowledge, which we call "intellectual disciplines."

Renaissance art turned more and more to secular subjects, often to scenes from classical mythology (as in many paintings by Botticelli), as well as landscapes, portraits, etc. Even when the plots were religious, new secular motifs were visible in them. It can be said without exaggeration that the place of the central symbol in the art of the Italian Renaissance is

m See o on \ t< е Ренессанса: Ben-David J. The sociology of science. Englewood Cliffs (N.J): Prentice-Hall, 1971.

Knsteller P.O. Renaissance thought: The classic, scolastic and humanist strains. n y.: Harper, 1961.

sa was occupied by the Madonna and child. In a purely religious sense, this was a serious departure from such subjects as the crucifixion of Christ, the martyrdom of saints, etc. The human family, and especially the relationship between mother and child, comes to the fore and even is glorified. Motherhood sought to make everyone attractive

nym, portraying Mary as a beautiful young woman who undoubtedly loves her child. Doesn't this symbolism reflect a further shift in Christian consciousness towards a positive affirmation of a secular world order that is correct, by its standards?

In its main characteristics, the Renaissance was not a movement towards synthesis, but rather a period of rapid cultural innovation. Such impressive changes could hardly have taken place without the involvement of the highest levels of culture - philosophy and theology - in the general process. This idea is confirmed by the dynamic character and diversity of scholastic philosophy. Although Thomism became the main formula of the late medieval synthesis, numerous other currents of thought continued to exist. Perhaps the most significant of these was nominalism, which, feeding on classical thought and themes gleaned from Islamic philosophy, constituted the most developed branch of scholasticism. It was more direct than Thomism, open to empirical research and free from Thomist efforts to create a complete Christian picture of the world.

In a wide variety of other spheres of cultural activity, the Renaissance produced not only the differentiation of the religious and the secular, but also their mutual integration. Just as the symbol of the Madonna meant greater involvement in "earthly affairs", new trends in monasticism gained more influence, primarily the Franciscan and Dominican orders, which showed an increased interest in charity and intellectual pursuits. The scientific works of the Renaissance humanists and jurists had deep philosophical and, in fact, theological overtones, which became especially noticeable when the first great achievements of the new science attracted attention and required interpretation. The condemnation of Galileo by the church is by no means a demonstration of simple indifference to his work. And the problems raised by Galileo are in no way connected with the earlier ideas of the Florentine N. Machiavelli, the first European "social thinker" who sought to

I'm McJIwain S.I. op. cit; Kristeller P. O. op. cit. 68

not to substantiate a predetermined religious and ethical point of view, but to understand how secular society really works.

The Renaissance was born in Italy and reached its highest development there. Very early, however, the same movement, most pronounced in painting and also interspersed with medieval culture, began north of the Alps. In Germany, it did not have such the highest achievements as in Italy, but here it gave the world outstanding artists - Cranach, Dürer and Holbein. It also penetrated early into Flanders, where it developed fully, and much later into Holland, where it continued during the period of Protestantism and flourished in full measure in the 17th century. Not only in Italy, this cultural movement originated in the social environment of the Italian city-states. Its expansion to the north also coincided almost exactly with the region of free urban communities, concentrated along the Rhine valley. Nothing like this happened to the visual arts in the predominantly feudal regions, which played a leading role in the formation of large territorial states.

The Reformation was an era of even more radical cultural change that profoundly affected the relationship between cultural systems and society. The main cultural innovation was theological in nature and consisted in the teaching that salvation is achieved, according to the Lutheran version, “only by faith”, and according to the Calvinist version of predestination, through direct communication of the individual human soul with God without the participation of any effort on the part of man. . This innovation deprived Protestant church and her clergy of "power over the keys of Paradise", that is, the mediating mission to secure salvation through the performance of the holy sacraments. Moreover, the "visible" church - a specific group of believers and their spiritual leaders - began to be thought of as a purely human association. The quality of holiness, the status of the church as "the mystical body of Christ" began to be assigned only to the invisible Church, the union of souls in Christ 54 .

Human society could not be based on two layers, as profoundly different, as Thomism claimed, in terms of their religious status - the church, both divine and human, and the purely human earthly world. Rather, it was a single society, all members of which

54 Mcllwam C . H. op. cit.; Kristeller P. O. Op. cit.

were both "bodies" in their capacity as worldly beings and "souls" in their relationship with God. This understanding represented a much more radical institutionalization of the individualistic components of Christianity than Roman Catholicism 33 . It also contained deep egalitarian tendencies, the development of which, however, required a long time and was carried out very unevenly.

A further consequence of the clergy's being deprived of their sacral power was the destruction of that part of the Roman Catholic tradition which was customarily called "faith and morals" and in matters of which the visible church took guardianship over all people. Although many Protestant movements have attempted to maintain ecclesiastical coercion in moral matters, the very inner charge of Protestantism has tended to regard them as a matter ultimately of the individual's personal responsibility. In the same way, Protestantism lost its legitimacy in the most important form of stratification within the medieval church - the opposition between laymen and members of religious orders. On the human level of "way of life" all "callings" received an equal religious status, and on the path of worldly vocation one could achieve the highest religious merit and perfection 36 . This attitude also affected marriage, Luther himself, as if creating a symbol of these changes, left the monastery and married a former nun.

These major shifts in the relationship between the church and the world are often interpreted as a serious weakening of the religious principle in favor of worldly pleasures. However, such a view seems to be false, since the Reformation was much more a movement to raise secular society to the highest religious level. In matters of religious faith, although not in everyday life, each person was obliged to behave like a monk, that is, to be guided primarily by religious considerations. This was a decisive turn in the process of consecrating things “of this world” with religious values \u200b\u200bthat began in the early stages of Christianity and building the “city of man” in the image God's 37

13 Webei M The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism N Y Cnbner , 1958 \ Be 6 ep M Protestant ethics and the spirit of capitalism / / Weber M Selected works of M Progress, 1990]

Ibid TioelRch E Op cit Vol 2 Troeltsch E Protestantism and progress Boston Beacon 1953 Paiwnf T Chnstiamtv//International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences N Y Macmillan 1968